I have always been very interested in explainability of algorithms, stemming from the curiosity of understanding how models work. I came to realize that the progress of machine learning is largely credited to the power of algorithms in capturing the delicate and complicated interactions between features. The most powerful of them all is the neural networks that does ‘automatic feature engineering’. On the one hand, it is slightly frustrating that I get a headache looking at a 4 layer decision tree, or trying to tease apart a neural network with only 6 neurons (tensorflow playground). On the other hand, it is very exciting to learn about the possibilities of explaining these ‘blackbox’ models with the right tools.

I would like to share this fascinating toolbox, SHAP, in this blog, while I shall recommend some great resources to start explorating this topic:

- A great online book by Christoph Molnar

- A short practical course on explanability from Kaggle by Dan Becker. It covers 3 tools: permutation importance, partial dependence plot and SHAP values. There are demos and exercises to help you learn about the tools.

Overview

SHAP is developed by researchers from UW, short for SHapley Additive exPlanations. As there are some great blogs about how it works, I will focus on exploring some visualisation built on SHAP, which I have demonstrated using the ‘HelloWorld’ for data science - the Titanic dataset. The code can be found in this notebook.

How does SHAP work?

It would be ironic if I don’t explain the tool that explains the blackbox models (it would be like $\text{blackblox}^2$). There will be a bit of maths so feel free to come back to it once you are convinced this is a useful tool.

SHAP belongs to the class of models called ‘‘additive feature attribution methods’’ where the explanation is expressed as a linear function of features. Linear regression is possibly the intuition behind it. Say we have a model house_price = 100 * area + 500 * parking_lot. The explanation is straightforward: with an increase in area of 1, the house price increase by 500 and with parking_lot, the price increase by 500. SHAP tries to come up with such a model for each data point. Instead of the original feature, SHAP replaces each feature ($x_i$) with binary variable ($z’_i$) that represents whether $x_i$ is present or not:

Here $g(z’)$ is a local surrogate model of the original model $f(x)$ and $\phi_i$ is how much the presence of feature $i$ contributes to the final output, which helps us interpret the original model.

Shapley value

The idea of SHAP to compute $\phi_i$ is from the Shapley value in game theory. To understand this idea, let us imagine a simple scenario of solving a puzzle with prizes. With Alice alone, she scores 60 and get £60. Bob comes to help and they scored 80. When Charlie joins, the three of them scores 90. Would it be fair to distribute the pay as £60, £20 and £10 to Alice, Bob and Charlie? Maybe, Charlie on his own can score 80! It would be only fair to consider different combinations of the three players to gauge their ability and contribution to the game.

Following this idea, the SHAP value evaluates the difference to the output $f_x$ made by including the feature $i$ for all the combinations of features other than $i$. This is expressed as:

To understand this equation, let us look at each part. $S$ is the subset of features from all features $N$ except for feature $i$, $\frac{\vert S\vert!\left(M-\vert S\vert-1\right)!}{M!}$ is the weighting factor counting the number of permutations of the subset $S$. $f_x(S)$ is the expected output given the features subset $S$,

which is similar to the marginal average on all other features other than the subset $S$. $f_x(S\cup\{i\}) - f_x(S)$ is thus the difference made by feature $i$.

Properties of SHAP values

In the NIPS paper, three desirable properties of SHAP values are given

- Local accuracy: the sum of the feature attributions is equal to the output of the model we are trying to explain.

- Missingness: features that are already missing (such that $z_i′ = 0$) have no impact.

- Consistency: changing a model so a feature has a larger impact on the model will never decrease the attribution assigned to that feature.

The author’s blog gives some insights why the properties are desirable. For example, if consistency is violated, we cannot compare the feature importance from different models.

Toy example: hand-calculation of SHAP values

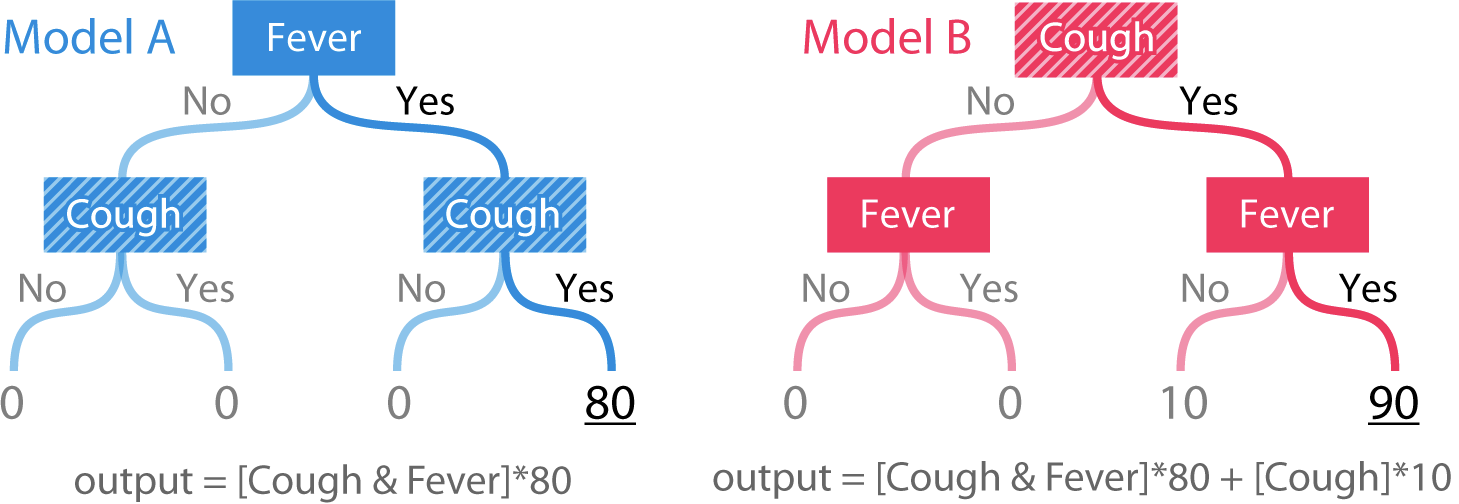

I shall demonstrate how SHAP values are computed using a simple regression tree as in the Tree SHAP arXiv paper. Here is what the two models look like.

If we only have one example at each leaf node, we can get intuitively that Fever and Cough are equally important for Model A while cough is more important for Model B. Let us focus on the ‘Fever = Yes, Cough = Yes’ example for Model A. The full permutations of the two features are empyty set({}), Fever only ({F}), Cough only ({C}), both Fever and cough ({F, C}). The expected output given ‘Fever = Yes’ only, $f_x(\{F = \text{Yes}\})$, is 40 and the same goes to ‘Cough = Yes’ only, $f_x(\{C = \text{Yes}\}) = 40$.

The expected values for Model A and B for different feature combinations are given in the table

| Feature combinations | {} | {F} | {C} | {F, C} |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A: Fever = Yes, Cough = Yes | 20 | 40 | 40 | 80 |

| Model B: Fever = Yes, Cough = Yes | 25 | 45 | 50 | 90 |

To compute the SHAP value for Fever in Model A using the above equation, there are two subsets of $S\subseteq N \setminus\{i\}$.

- $S =$ { }, $\vert S\vert = 0, \vert S\vert! = 1$ and $S\cup\{i\} =$ {F}

- $S = $ {C}, $\vert S\vert= 1, \vert S\vert! = 1$ and $S \cup\{i\} =$ {F, C}

Adding the two subsets according to the definition of SHAP value $\phi_{i}$,

Similarly,

For Model B

Comparison with other feature importance metrics

The paper also shows, using this extremely simple example, that SHAP overcomes the inconsistency problem in other feature importance metrics.

-

Saabas refers to computing the contribution of each feature based on the change in output given in each tree split. In Model B, the first split on Cough increases the output from 25 to 50 and the second split on Fever increases the output from 50 to 90. Thus the feature contribution are $\phi_F = 40$ and $\phi_C = 25$. Its inconsistency is likely because it only considers the single tree configuration.

-

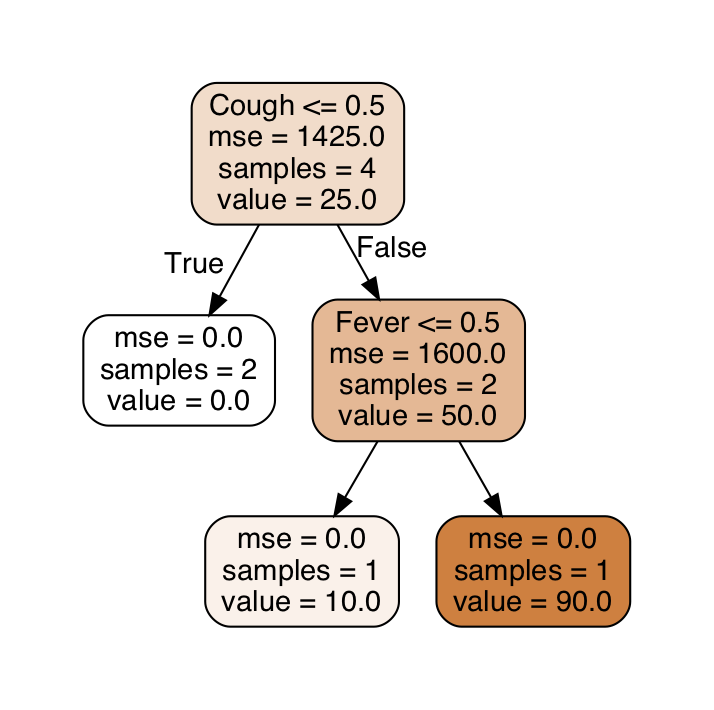

Gain-based method is the default feature importance metric in Scikit-learn, which is evaluated on the entire model. For regression, it is computed as the reduction in MSE (mean squared error) based on each feature.

After the first split on Cough, the overall MSE reduces from 1425 to 800 and the second split reduces MSE from 800 to 0. Thus the feature importance of Cough = 625/1425 = 44% and Fever = 800/1425 = 56%. If we compare this to the model-wise SHAP values, $\text{mean}(|\text{SHAP values}|)$, $\phi_{F, model}$ = 20 and $\phi_{C, model}$ = 25. Again gain-based is inconsistent.

- The only other metric that is consistent is the permutation test. Both methods are computationally intensive but SHAP is better as it gives far more detail/insight.

This link has the code for the basic example.

SHAP in action: Titanic model

As this is a demo for how SHAP works, I have done minimal feature engineering. To see how to improve the accuracy with feature engineering, read some Kaggle kernels. You can find the code for reproducing the results here.

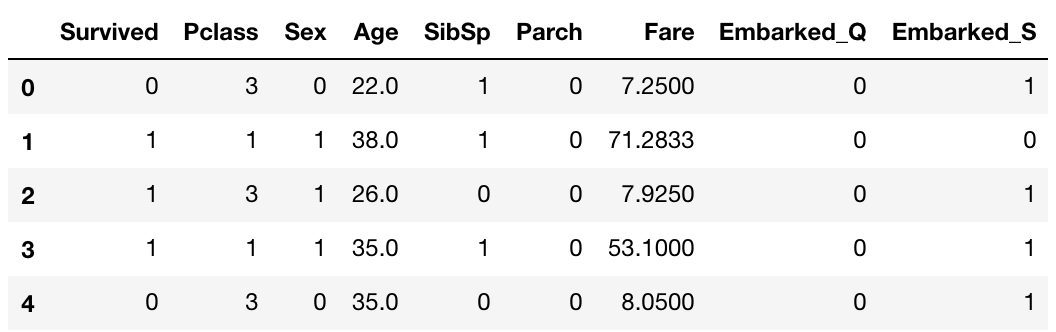

Here is the raw data

Survivedis what we are trying to predictPclass: 1 = 1st, 2 = 2nd, 3 = 3rdSex: 0 = male; 1 = femaleSibSpis the number of siblings + spouses aboard the TitanicParchis the number of parents + children aboard the TitanicEmbarked_Q: QueenstownEmbarked_S: Southampton

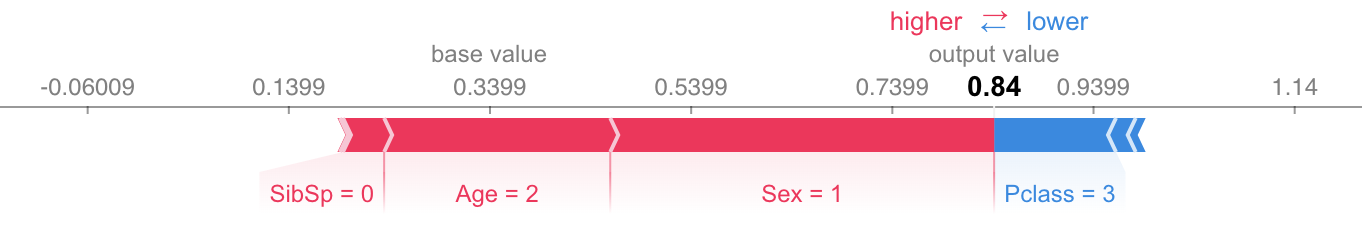

This plot shows the interpretation of the prediction using logistic regression on one example using SHAP. We can see that the gender (female) and age (2) has the most positive impact on the survival while 3rd class has the most negative impact.

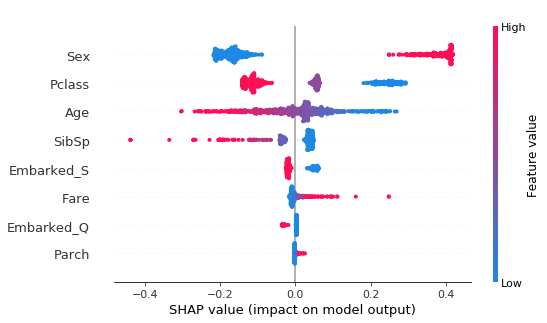

If we aggregate such examples for the entire training data, we can visualise the effect of features among population. Some obervations are

- The gender has the maximum impact.

- A high SibSp number can be very significant.

- The effect is largely linear, as expected from logistic regression but SHAP shows some non-linearity arising from feature interactions.

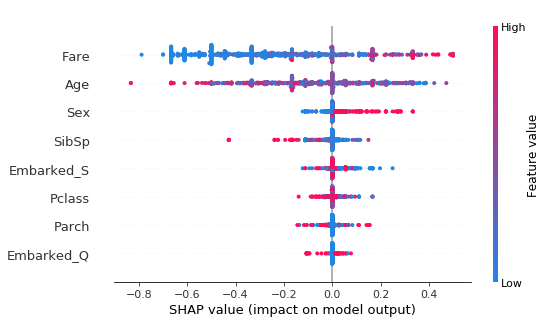

The SHAP summary from KNN (n_neighbours = 3) shows significant non-linearity and the Fare has a high impact. It alerts me that I should have done normalization on the features.

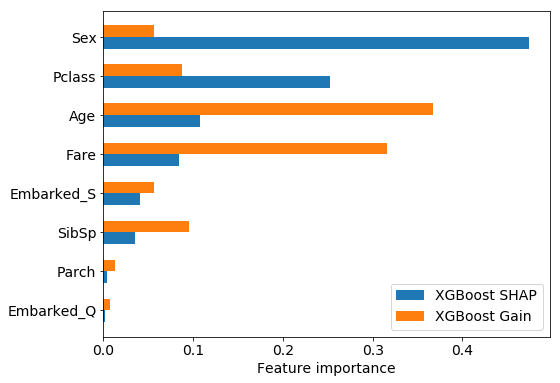

The above two examples used the KernelExplainer interfaced with Scikit-learn and the TreeExplainer with XGBoost uses the accleration described in the paper. Here, I shall illustrate again the drawback of gain-based method in the next figure. The impact of Sex and Pclass are undervalued by the gain-based feature importance compared to SHAP.

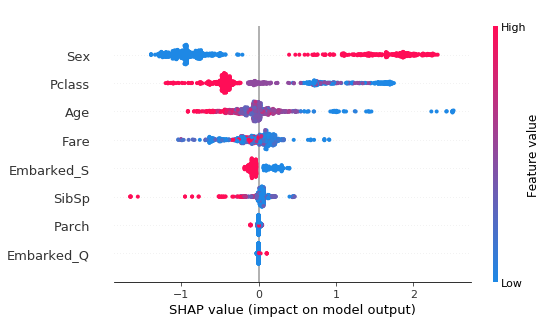

The SHAP summary plot is also very interesting. XGBoost model captures similar trends as the logistic regression but also shows a high degree of non-linearity. E.g., the impact of the same Sex/Pclass is spread across a relatively wide range.

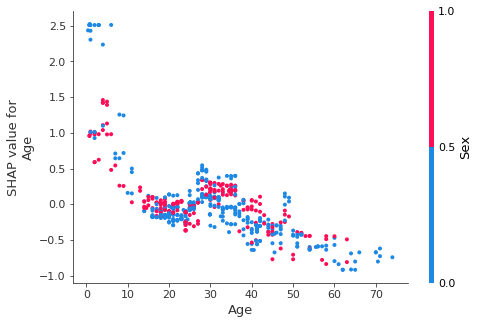

As the Age feature shows a high degree of uncertainty in the middle, we can zoom in using the dependence_plot. Here, the SHAP values are plotted against Age colored by gender. A significant positive impact can be seen for Age < 10.

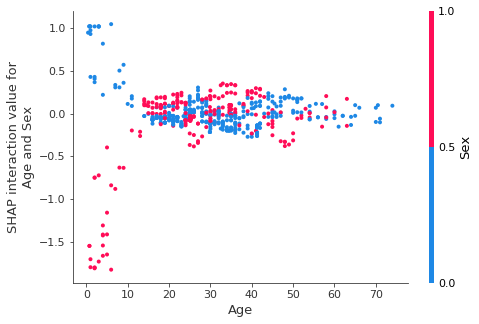

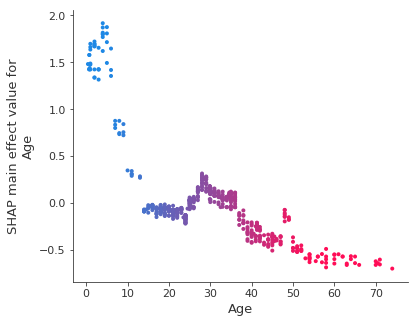

The dispersion of SHAP values for a certain age is due to feature interaction and it is captured by the Shapley interaction index (see Appendix). The first figure shows the interaction between Age and Sex, where there is little interaction between the two when Age > 10. For the young age group, the SHAP value for male is positive but is negative for female. If we remove the interaction of all other features, the remainder, i.e., main effect, shown in the second plot, has little dispersion.

|

|

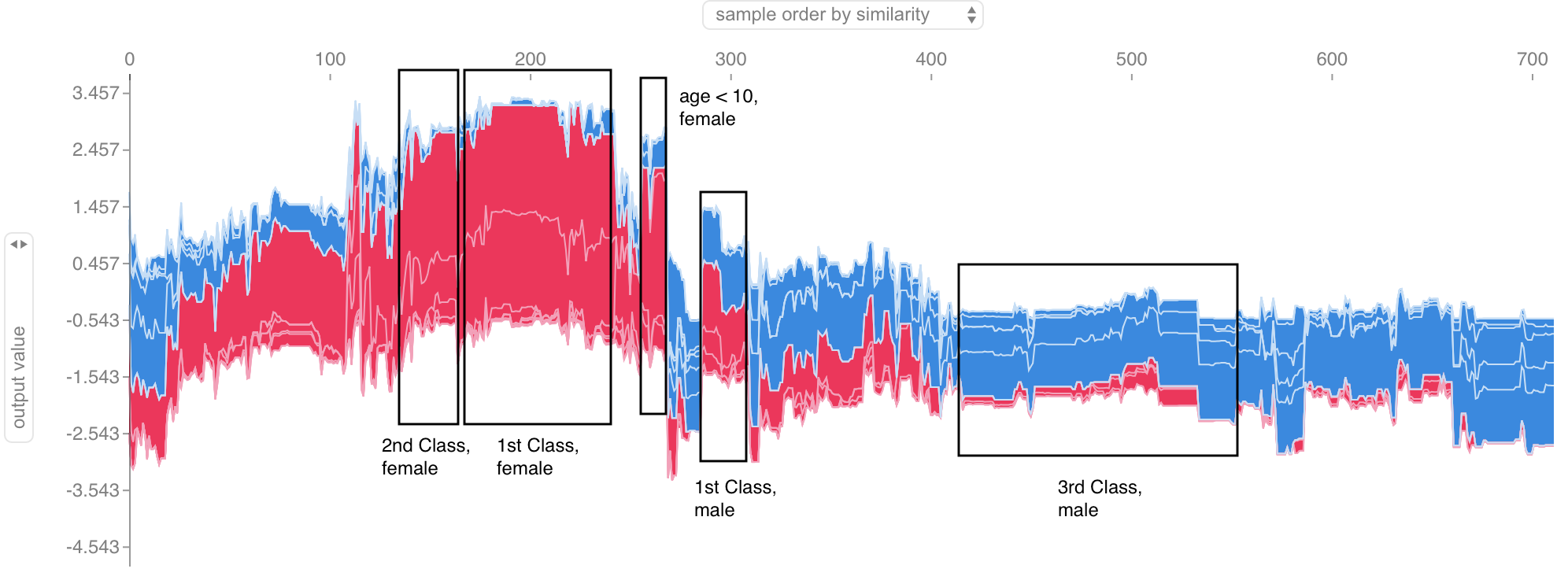

There is one more hidden gem in the paper. As SHAP values try to isolate the effect of each individual feature, they can be a better indicator of the similarity between examples. Thus SHAP values can be used to cluster examples. Here, each example is a vertical line and the SHAP values for the entire dataset is ordered by similarity. The SHAP package renders it as an interactive plot and we can see the most important features by hovering over the plot. I have identified some clusters as indicated below.

Summary

Hopefully, this blog gives an intuitive explanation of the Shapley value and how SHAP values are computed for a machine learning model. I shall emphasize again the consistency of SHAP compared to other methods. Most importantly, try creating some visualisations to interpret your model! There are more examples by the authors and the package is very simple to use.

As a final remark, I still think that one should use more than one tool for interpreting the model. And these tools should not replace the hardwork figuring out how the model works .

References

Besides the papers referred, here are some blogs that helped me:

- https://towardsdatascience.com/interpretable-machine-learning-with-xgboost-9ec80d148d27

- https://medium.com/@gabrieltseng/interpreting-complex-models-with-shap-values-1c187db6ec83

- https://towardsdatascience.com/one-feature-attribution-method-to-supposedly-rule-them-all-shapley-values-f3e04534983d

Appendix: interaction index

The Shapley interaction index between two features $i, j$ is defined as

where

which captures the effect of feature $i$ with and without the presence of feature $j$.

The main effects can then be computed by subtracting all the interaction terms